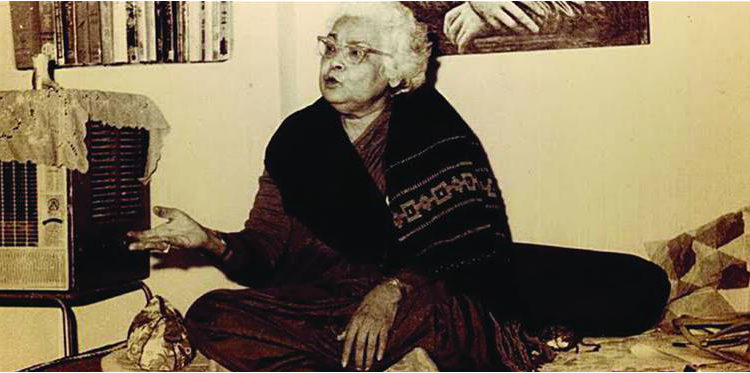

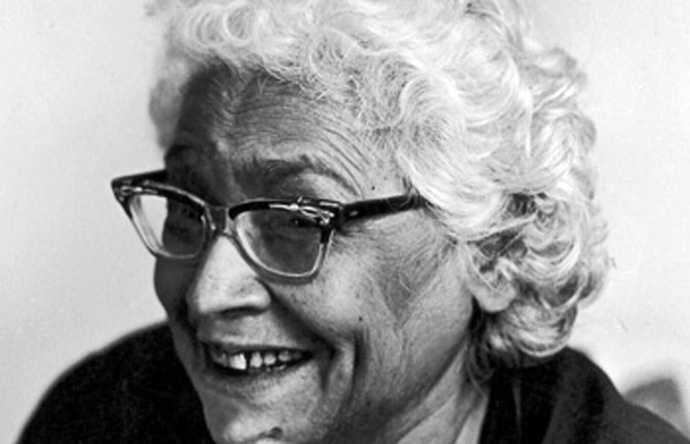

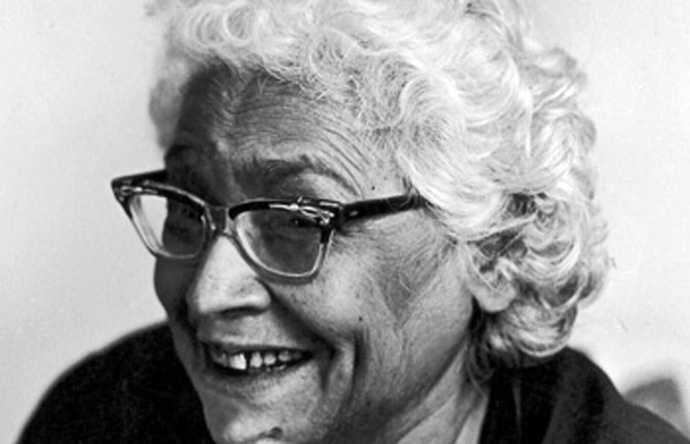

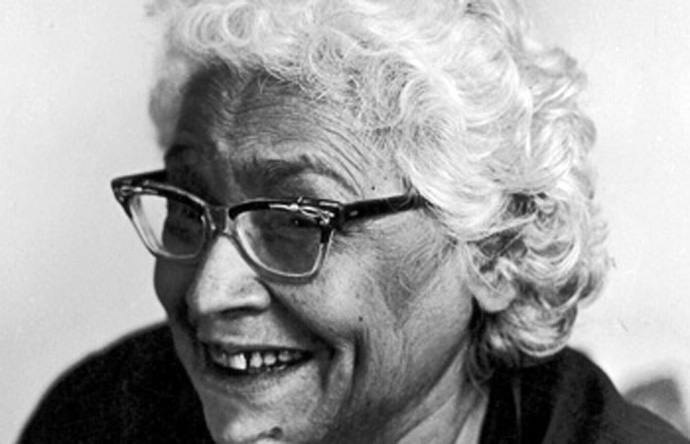

“I have always thought of myself first as a human being and then as a woman,” wrote the famous Urdu feminist author Ismat Chughtai. August 21, 2020, marks her 109th birth anniversary who has formed the quintessence of women empowerment and freedom of speech. Considered to have spearheaded the modern Urdu short story scenario, Chughtai flaunted her audacious demeanor till her last breath. Ismat Chughtai was a dissenter, an educationist, and a symbol for the emancipation of women. She strived to apprehend the complexities of a woman’s personality and psyche, along with their impediments. All of her writings rendered a certain kind of convolution to the protagonists. Chughtai was the kind of writer who always caused a commotion with her intense and defiant women protagonists in her blunt writing style.

Her autobiography “Kaghazi hai pairahan” (or The Paper Attire) taken from the second line of the couplet in Ghalib’s assemblage of poetry, provides the reader with a context about her astounding prowess to disrupt the ideas that comprised civility along with questioning the hypocritical society dauntlessly. Throughout her childhood, she was procumbent to persistent scorn because of showing the least interest in cooking, embroidery, and stitching similar to her conventional sisters. Chughtai had a propensity for picturing the emotional form of stories she had heard. Her fondness for the acquisition of knowledge from whatever sources possible made her stern about not giving up her education despite everything. Ismat Chughtai vehemently revolted against the ethical and patriarchal standards of morality and propriety. She wrote when there weren’t many writings about women or for women.

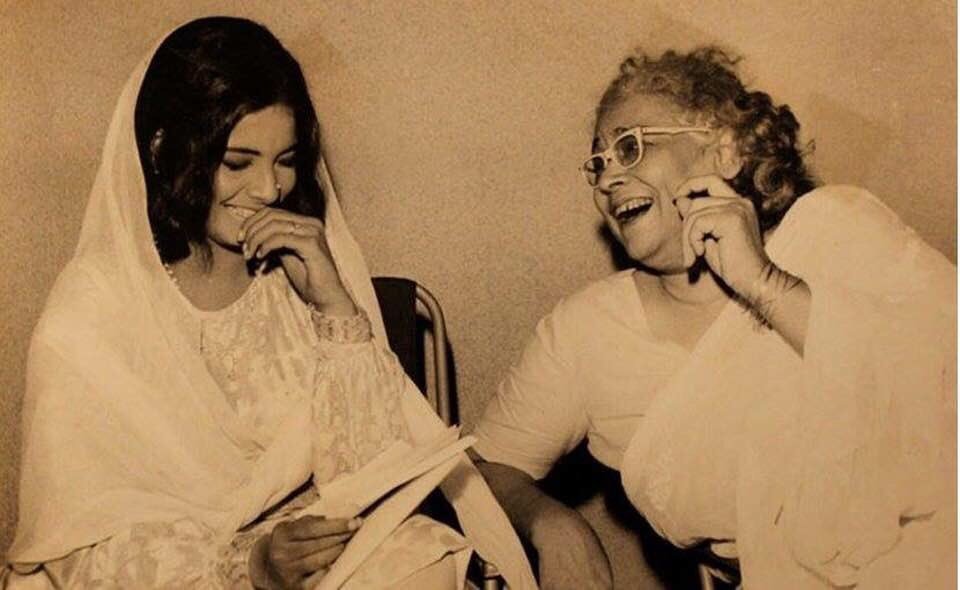

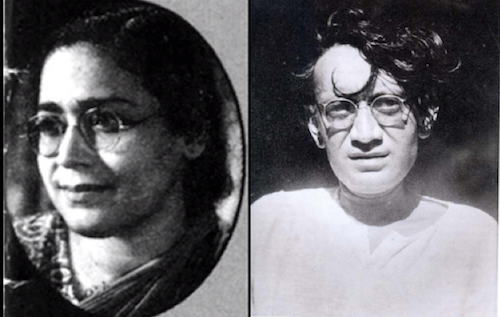

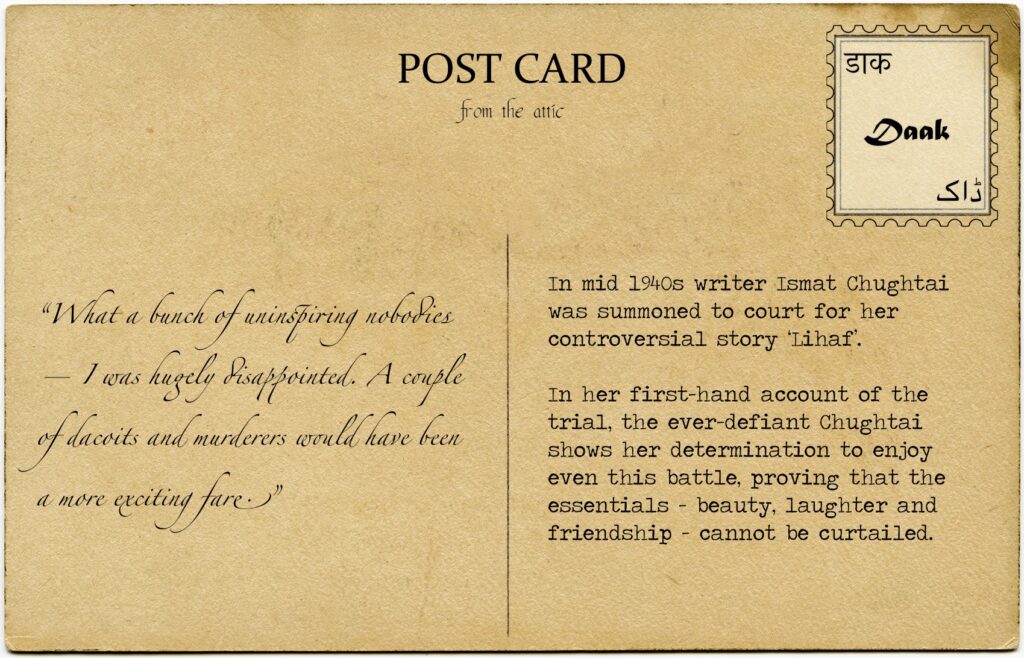

Like her peers, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, and Saadat Hasan Manto, Chughtai was incredibly impacted by Western authors of the nineteenth century, which serves as the elucidation of why the subjects of sexuality are so predominant in her compositions and suggest her cognizant determination of the equivalent. Her Urdu short story ‘Lihaaf’ (or ‘The Quilt’) (1942) was a noteworthy work that highlighted examples of female sexuality and lesbianism, any semblance of which hadn’t been seen so straightforwardly in Urdu writing, particularly by a female essayist. The then British government pressed serious charges against Ismat Chughtai for which she had to go to Lahore court to defend herself. Even though her close friend, Saadat Hasan Manto was also facing the same charges (which was obscenity) for his story ‘Bu’( or ‘The Odour’), she was subjected to more sneering and scoffing because of being a woman. But her sense of resoluteness was something remarkable because of which she wasn’t ready to apologize or back down without being proved by the court because of her charges. Instead, she was just elated to get a chance to meet Manto whom she couldn’t reach out to after partition. When Chughtai wrote Lihaaf, she confessed to not knowing much about lesbianism and female homosexual desires. She said, “When I wrote Lihaaf, this thing [lesbianism] was not discussed openly. We girls used to talk about it and we knew there was something like it, but we didn’t know the whole truth…

In ‘Gharwali( The Homemaker), Mirza, as other male characters in Chughtai’s different stories, wears an attire of devotion. The passage of an explicitly freed Lajo as his local assistance modifies his attitude. Lajo is furious, vocal in her interest for sex, and disdains to wear contracting pants instead of a free streaming lehenga. The story is bound with dim humor and sensuality. It is an adept depiction of human feelings, for example, envy, obsessiveness, and sexual want. Mirza’s endeavors to tame Lajo into turning into a ‘great’ lady bomb wretchedly. Through Mirza, Ismat Chughtai reveals the lip services of the amenable society that on one hand, requests spouses to be modest and however allows its men to men. In ‘Vocation’, the story is described from the point of view of a lady who sees mistresses with mystifying scorn. Priding herself for having a place with the noble pursuit of teaching, she claims and practices regular profound quality and modesty before marriage. Nonetheless, she is flung into a personality emergency when a gathering of ‘tawaifs’ move into the area and attempt to produce a kinship with her. The story is intriguing as it sets the sharp doubles of perfect gentility and undermined womanhood just as of good callings, such as societal conventions of good pursuits like teaching and evil ones like prostitution. By utilizing a female storyteller, Chughtai unequivocally portrays that ladies disguise disdain towards other ladies through patriarchal molding, and in this way, the male-centric force structure is maintained. The story is additionally one of a kind as far as account style and the plot has an O Henry-Esque curve to it at long last.

When Chughtai undertook writing as a job, Urdu literature was, at that point, an impression of the traditionalist outlook of the Urdu-talking masses, where themes like homosexuality didn’t make for ideal conversations among people. In no way, did she yield to this subjugated system or tries to conceal it in her works. Her works, be it her books or her short stories, are for the most part wonderful depictions of gentility at its rawest, generally legit, and are completely touched with resistance and interest for progress and balance. When questioned about ‘obscenity’ in her stories in an interview, she said, “In my stories, I’ve put down everything with objectivity. Now, if some people find them obscene, let them go to hell. I believe that experiences can never be obscene if they are based on the authentic realities of life…”

Ismat Chughtai is not only remembered for her dexterous writing and beautifully crafted stories but mainly for the staunch feminist that she was. She is remembered for simulating women to shatter the orders and barriers placed for them in this deceitful society.